The Murder of Amelia Wilson

In 1969, Charles Town, WV was shaken by the murder of Amelia Wilson, leaving her sons, Gary and Steven, to navigate a life marked by loss. Despite minimal media attention and no recent investigations, this article aims to shed light on the case, hoping for closure after 55 years.

This story received minimal media attention when the crime occurred, with the only subsequent coverage being an editorial two years later, in 1971. Present-day examinations of the event are nonexistent, making it a story that deserves to be told before it disappears from the collective memory of Charles Town residents who lived through the events over 55 years ago. This article represents a departure from my usual approach of relying solely on existing sources for my stories. Having had the chance to interview the victim's son, I aim to add depth and personal insight to Amelia's story, hoping to honor her memory and the impact of the events on those who knew her.

After reading Amelia's story, be sure to check out the latest update, which explores new information that may link the murder to a local police officer,

Nestled in the heart of Jefferson County, West Virginia, Charles Town embodies the quintessence of small-town America with its rich history and scenic beauty. Known for its tranquil atmosphere and tree-lined streets, this community is a place where history intersects with the quiet rhythms of everyday life. In the late 1960s, Charles Town, like much of the country, was experiencing the winds of change brought about by the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, and the burgeoning counterculture. Yet, amidst these national upheavals, Charles Town remained a bastion of stability and tradition, a place where neighbors knew each other by name and local businesses thrived on family patronage. But that would all change on the night of August 27, 1969, when a crime of shocking brutality occurred. Mrs. Amelia Wilson, a 33-year-old local resident known for her kindness and quiet demeanor, was brutally murdered.

This event became a somber chapter in Charles Town's history, a reminder of the fragility of small-town serenity in the face of inexplicable violence. As the years have passed, the case remains one of the few unsolved murders of the town.

The Murder

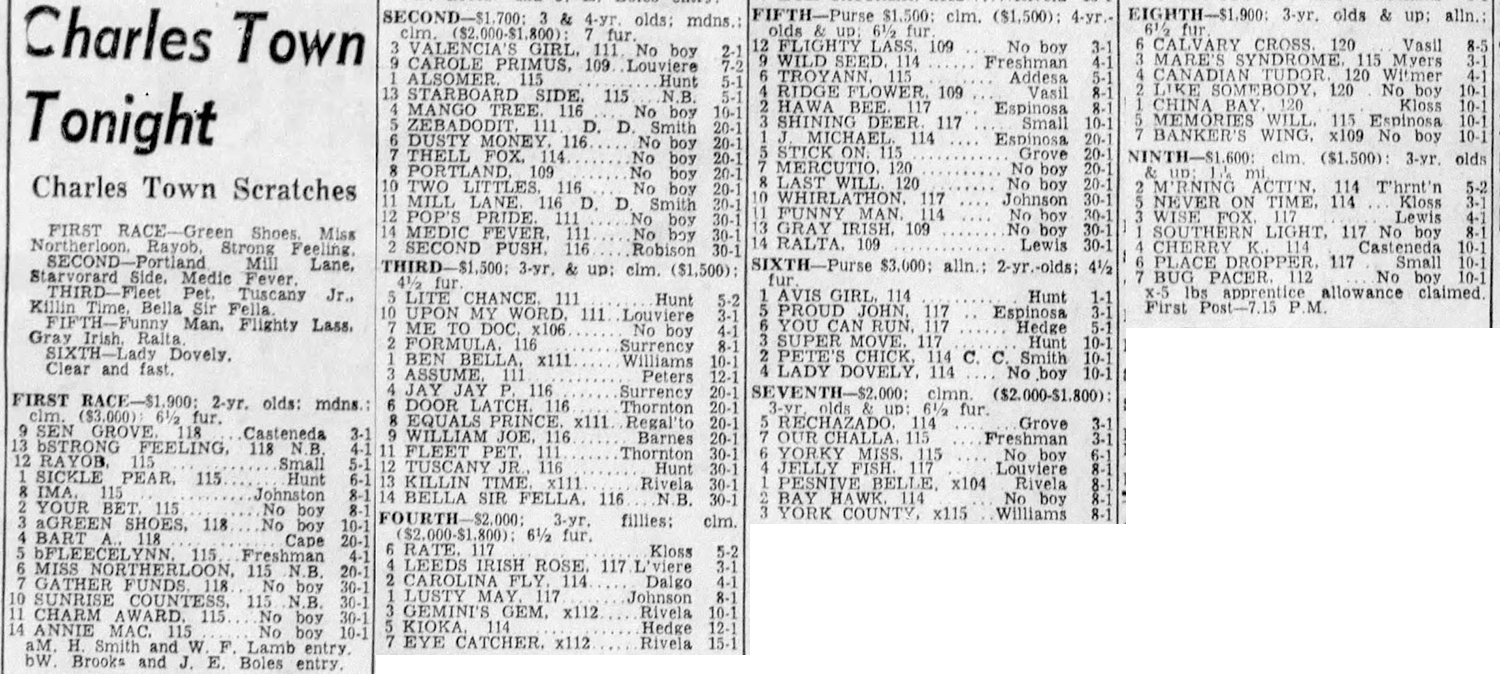

Amelia Wilson clocked out from her shift at the Charles Town Race Track, also known as the Turf Club, at 11:00 PM on a warm Wednesday night, alongside her colleagues Mary Espinosa and hostess Barbara Cape. Exiting to the parking lot, they encountered Catherine, a new waitress, waiting by herself for her husband. Amelia, concerned for her safety, advised, “You shouldn’t wait there alone,” a moment that Barbara remembers clearly. Barbara accompanied Amelia briefly after leaving work, during which Amelia mentioned wanting to grab a drink. She was excited about her day off the next day, especially about taking her sons to their first day of school on Thursday. This account was shared by her coworkers in an interview conducted the day following the murder.

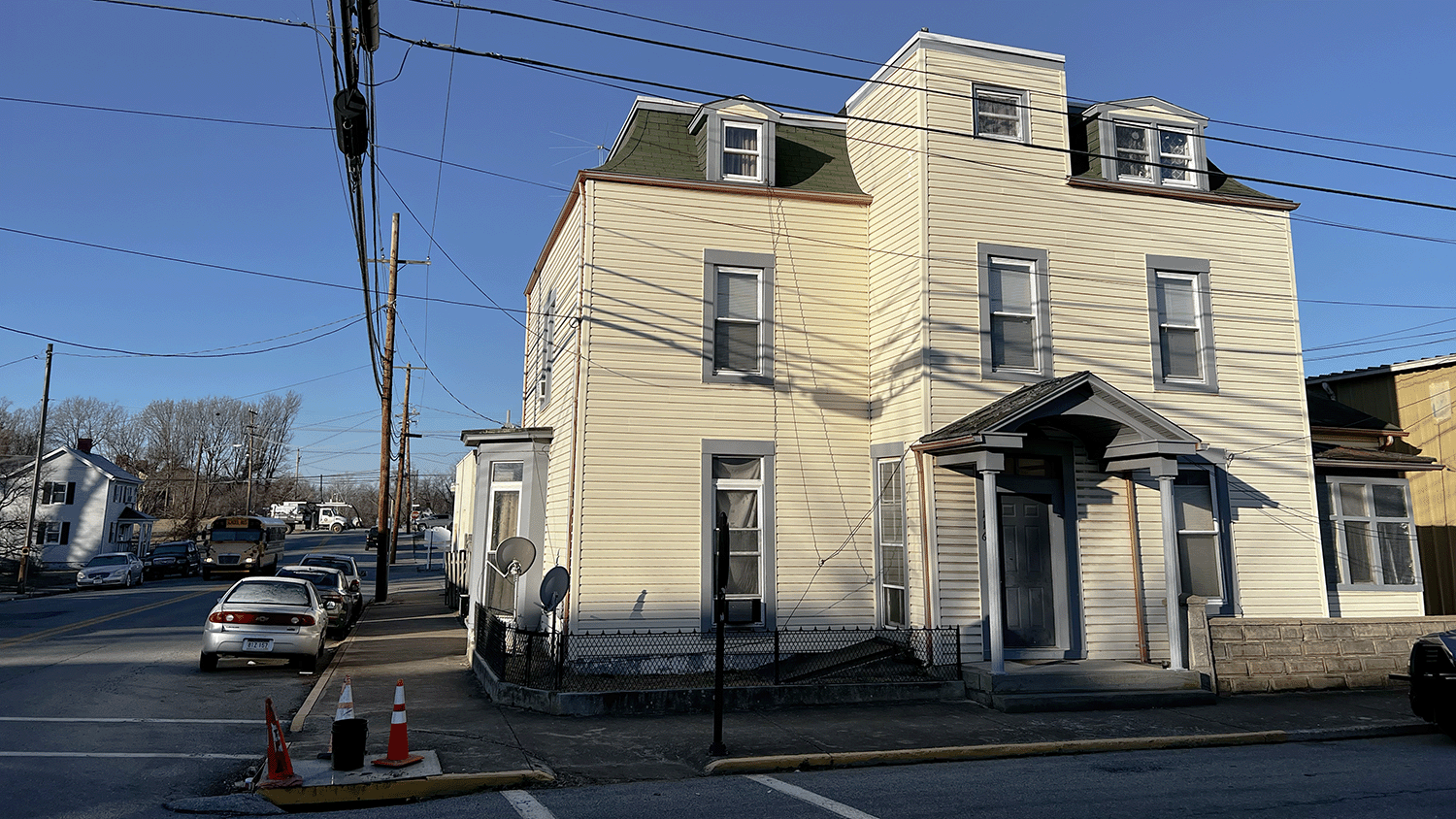

However, given the timing of the incident, it seems Amelia decided against having that drink and instead headed straight to her third-floor apartment at the Fritts Apartments, situated at the corner of Congress and Lawrence streets, where she resided with her young sons, Steven and Gary. Around the time she was attacked, other residents reported hearing a disturbance but did not investigate further.

The night quickly took a horrifying turn in the brief walk from her car to her front door, a distance of no more than 100 feet. Amelia was brutally attacked, leaving her unconscious and critically injured. The assailant not only assaulted her but also removed her clothing in a methodical and without damaging them, later found neatly arranged on a nearby fence.

It was in the bushes beside her apartment where Amelia was eventually found, her black and white waitress uniform stained with blood, evidence of the violent encounter she had endured. Upon discovery, Amelia was swiftly taken to Charles Town Hospital for emergency treatment. She had sustained a severe injury – a one-inch wound on the back of her head, inflicted by a hard object. Due to the gravity of her condition, she was promptly transferred to Washington County General Hospital in Hagerstown for more specialized care.

Tragically, she succumbed to her injuries in the ambulance en route to Hagerstown, passing away around 1:30 AM on August 28 near Boonsboro. The official cause of death, as determined by the medical examiner, was a combination of a subdural hematoma, cerebral edema, and acute pulmonary edema. These conditions, stemming from the traumatic head injury, indicate significant brain swelling, internal bleeding within the skull, and a rapid accumulation of fluid in the lungs, all contributing to her untimely death.

The peculiar circumstances of the incident, particularly the removal and orderly placement of Amelia's clothing, added a layer of mystery and horror to an already gruesome crime. Despite this, the autopsy reported no evidence of sexual assault. The nature of the attack, seemingly random yet pointedly brutal, left the community and investigators grappling with numerous unanswered questions. The lack of immediate witnesses and concrete evidence only compounded the mystery.

Amelia Wilson

Amelia Kathleen Braithwaite Wilson entered the world on April 20, 1936, in Berkeley County, West Virginia. Born to Martin Ellis Braithwaite and Charlotte Virginia Prather, her upbringing in Charles Town was likely shaped by the local values and community spirit emblematic of mid-20th century rural America. Growing up in a family with deep roots in the area, her early years were likely a blend of simplicity and the everyday challenges of the time.

In 1955, at the age of 19, Amelia married Robert Eugene Wilson in Martinsburg, West Virginia. This marriage, however, was not destined to last, ending in divorce before Robert remarried in 1959. Amelia was blessed with two sons, Gary Eugene Wilson (born 1956) and Steven Wayne Wilson (born 1959). Records indicate that she had two additional children, Melinda “Linda” (born in 1961, adopting the surname Tanner upon her adoption, and known as Minnick at the time of her death) and Steven Pyles (born in 1964). Both were given up for adoption at birth, a decision that likely had a significant emotional impact on her.

Life as a single mother marked a significant chapter in Amelia's story. Her son Steven recalls her as a hardworking and caring mother, who balanced her job at the Charles Town Turf Club with additional house cleaning work to provide for her family. Known for her speed and efficiency at her waitress job, she was affectionately nicknamed 'Speedy' by her coworkers. Despite the demands of her work, she found time for tender moments, such as taking Steven to the diner for a treat – a burger, fries, and a shake.

Amelia's dedication to her family was further exemplified in her efforts to guide Gary, who was struggling with behavioral issues and on the brink of being sent to a juvenile facility. Her commitment to her children's well-being was a defining aspect of her character according to her coworkers.

Remembered by her friends and coworkers as a reserved and unemotional woman, Amelia's closest friend, Beulah Walker, described her as fiercely independent. Content with her life and not seeking remarriage, she found satisfaction in her independence and the life she built for herself and her sons. Yet, she was not entirely a loner; she enjoyed socializing occasionally and had plans to spend quality time with her sons and friends during her days off.

Her physical appearance, described as unremarkable but highlighted by her blonde hair, soft skin, brown eyes, and distinctive bangs, made her a familiar and comforting presence to those around her according to one of her acquaintances who was interviewed at the time.

The narrative of Amelia's life, as shared by her son Steven, paints a portrait of a woman who was much more than the victim of a tragic crime. She was a loving mother, a hard worker, and a valued member of her community, whose life was marked by both joy and challenge. Her untimely and tragic end only adds to the poignancy of her story.

The Investigation

The grim discovery of Amelia Wilson, lying in the bushes beside her residence at the Fritts Apartments, marked the beginning of a perplexing investigation for the Charles Town Police Department. Patrolman Charles Henry, the first officer at the scene, responded to a distress call made at 11:35 PM, reportedly from someone who sounded like a young boy. He found Amelia unconscious, bleeding, and showing clear signs of a violent assault. In the autopsy the examining physician stated that it was impossible to determine the kind of weapon used.

In a disturbing display, her clothes were methodically removed and neatly hung on a fence, indicating a deliberate and unsettling action by her assailant. Henry observed Amelia’s white Chevrolet parked on Congress Street, its door ajar, with blood stains on the sidewalk and the vehicle's exterior. This suggested that the attack possibly began as Amelia was removing items from her car, highlighting the suddenness and brutality of the assault.

Significantly, as recounted by her son Steven, Amelia had a considerable amount of tip money, in the form of a roll of cash, which was not taken by the attacker. This detail is particularly striking, as it dismisses the possibility of robbery as a motive, adding to the perplexing nature of the crime.

The attack's proximity to her home, coupled with the lack of noticeable disturbance to nearby residents, emphasized the stealth and swiftness of the attack. While some residents reported hearing noises around 11:10 PM, none deemed them suspicious enough to warrant further investigation. Henry theorized that the attacker, after striking Amelia, dragged her to the side of the apartment complex before removing her clothing.

The case, marked by scant evidence and few leads, posed a significant challenge to the Charles Town Police Department. The peculiarities of the crime, especially the removal and placement of Amelia's clothing, contrasted starkly with the autopsy results, which reported no evidence of sexual assault.

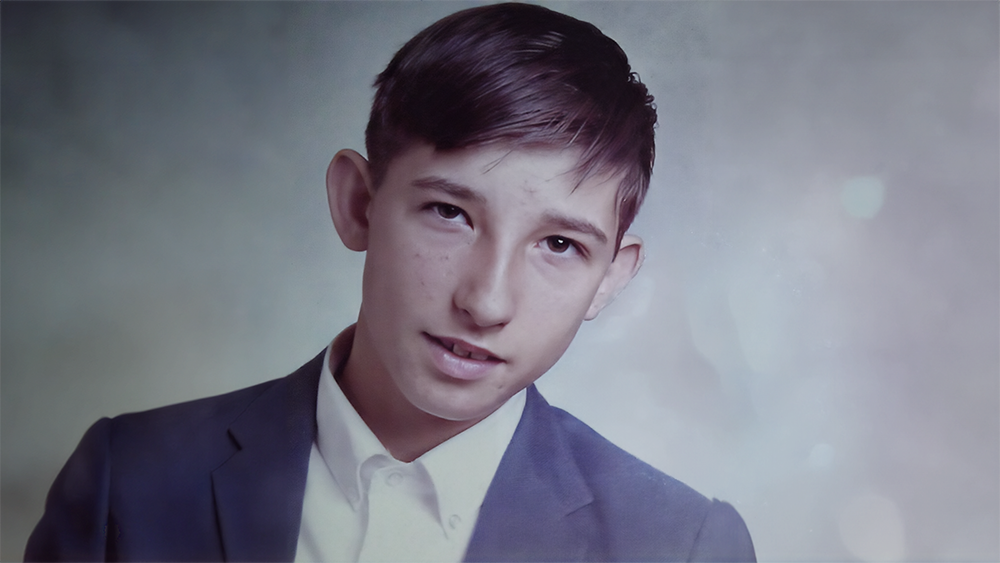

At just 10 years old, Steven Wilson experienced a night that would forever mark his life. On the evening of his mother Amelia's murder, he and his 13-year-old brother Gary, who often stayed up late due to their mother's evening work shifts, had gone to bed early for the first time, obeying her on the eve of a new school year. This rare compliance was interrupted by the sudden arrival of police cars, abruptly jolting them into a chaotic and fearful scene.

Steven vividly recalls peering out the window, witnessing the police following a blood trail. His recollection then shifts to a moment when two State Troopers entered their apartment, asking about a white Chevrolet. Upon confirming it was his mother’s, Steven rushed past them downstairs, where he saw her car with its door open. Driven by a sense of dread, he moved around the building, where he caught a glimpse of his mother, before returning to sit on the front porch in a state of shock.

Today, Steven tries to distance himself from these harrowing memories, as dwelling on them feels surreal. It is this detachment, he admits, that has enabled him to find some form of peace with the unsolved murder of his mother. This tragic night not only stole away their mother but also the remnants of their childhood innocence.

As the investigation unfolded with the assistance of the West Virginia State Police, the case stubbornly remained unsolved. The dearth of tangible leads or notable suspects, compounded by silence within the community, relegated the case to a cold status. The absence of both a clear motive and a discernible suspect left law enforcement and the townspeople wrestling with a tragedy that, at the time, cast a shadow over Charles Town.

Nearly two months following the murder, a concerted effort to break the silence materialized in the form of a $1,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the murderer. This reward, funded equally by Amelia's family and the Jefferson County Court, reflected a significant incentive in the quest for justice. Adjusted for inflation, this amount equates to over $8,000 in today's currency, aligning with contemporary standards for rewards in similar cases.

By 1971, two years after the murder, Charles Town Police Chief Perry Ott acknowledged the ongoing nature of the investigation. He admitted to having a suspect in mind but expressed frustration over the insufficient evidence required to proceed legally. This acknowledgment underscored the enduring complexity and unresolved nature of the case.

Steven has harbored suspicions about the identity of his mother's murderer, focusing on Lewis Delvin Parrill, who had a relationship with his mother and was seen as a prime suspect due to their allegedly abusive dynamic. However, Parrill later claimed he was in New Jersey when the murder occurred. In contrast, Steven dismissed the idea that Calvin Nelson Hinton, despite being implicated by local gossip, had any involvement. Steven had warm memories of Hinton, who had treated him with a fatherly kindness. Another suspect mentioned by the community was Ralph Lindberg “Buzzy” Whitmore, a local police officer, though the basis for his suspicion seemed to rest on unsubstantiated rumors rather than concrete evidence. Steven himself was unfamiliar with Whitmore, highlighting how small-town rumors can proliferate without clear foundation.

Despite these various suspicions, the truth about the murder remains out of reach. Hinton's life was cut short in 1974 when he was struck by a Baltimore and Ohio freight train while under the influence of PCP. Whitmore died in 1997 at 70, and Parrill lived until 2020, dying at 87, effectively ending any chance of legal resolution with these individuals in this case.

Steven revealed that at one point, he and his brother became the focus of the investigation. He recalled how the state police would take him in for questioning every day over a long period, subjecting him to extensive interrogations. He felt that the authorities were attempting to attribute the crime to him and his brother, particularly due to Gary's history of criminal behavior.

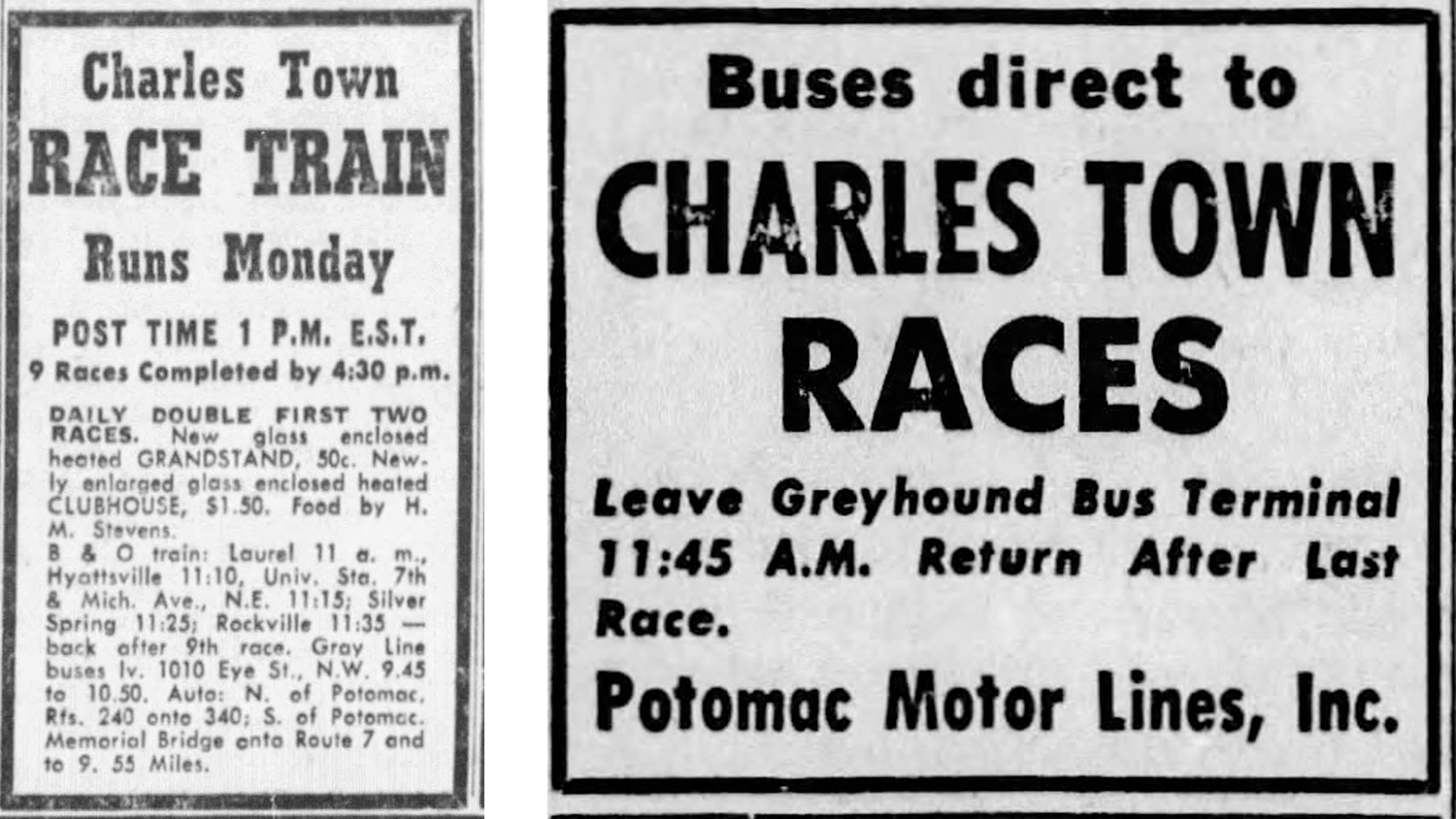

Charles Town, known for its two popular racetracks, was a magnet for visitors from afar, especially those transported by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad's race trains. These trains transported crowds from Baltimore and Washington, underscoring the racetracks' widespread appeal. Although the train service had ceased three years prior to Amelia's murder, there is evidence that race buses might have continued to transport outsiders to the area, in addition to those who now drove in—a factor likely contributing to the decline of both train and bus services. On the night of Amelia's murder, a night race scheduled for 7:15 PM would have attracted a significant number of out-of-town visitors. Working as a waitress in the Turf Club lounge, Amelia could have encountered someone with malevolent intentions, possibly a visitor there for the race, who might have followed her home, leading to the assault as she exited her car.

The crime's ritualistic elements suggest it was more complex than a mere crime of opportunity. The meticulous removal and placement of Amelia's clothing, along with the absence of similar crimes in the area, both before and after, lend credence to this view. Additionally, the likelihood of unfamiliar individuals in Charles Town around the time of the murder supports the notion that the perpetrator might not have been a local, further complicating the investigation

As decades passed, the murder of Amelia Wilson not only remained unsolved but also began to fade into the background of Charles Town's collective memory. Even the current Chief of the Charles Town Police was not familiar with the incident. In response, a renewed attempt was made to unearth any overlooked details or forgotten evidence. A West Virginia Freedom of Information request was submitted to the Charles Town Police, the Jefferson County Sheriff, and the West Virginia State Police. This effort was driven by the hope that a neglected file or piece of evidence, once brought to light, might provide new insights into the case.

However, the responses from these agencies painted a bleak picture regarding the availability of records. None of the contacted departments had retained any documents related to Amelia Wilson's case. Charles Town Police Chief Christopher Kutcher stated that an exhaustive search for any case files within his department had been conducted. Unfortunately, it was concluded that the files might have been lost amidst the department's multiple relocations over the years. According to Chief Kutcher, their archives held no records dating back further than the mid-1970s.

The records custodian at the Jefferson County Sheriff's Department stated that the case fell under the jurisdiction of the Charles Town Police Department. Consequently, they would not possess any records related to the incident.

The possibility remained that the West Virginia State Police, having been involved in the investigation, might possess some records. However, this avenue also led to a dead end. The custodian of records at the State Police eventually responded with the disheartening news that they could find no records pertaining to the murder.

The absence of records significantly dims the prospects of solving this decades-old mystery. With no case files to revisit, the investigation into Amelia Wilson's tragic death seems to have reached an impasse. The lack of documentation not only hinders any fresh investigation efforts but also symbolizes the gradual fading of this case from the institutional memory of the law enforcement agencies involved. It underscores the harsh reality that, with each passing year, the likelihood of uncovering new evidence or leads diminishes, leaving those who seek justice and closure with more questions than answers

The Aftermath

The brutal murder of Amelia Wilson not only robbed her sons, Gary and Steven, of their mother but also marked the end their childhood. Already without a father figure, the boys were now orphans and whatever normalcy they had was now shattered.

Contemporary reports reveal that less than 24 hours after Amelia's death, a man from Washington circulated a basket at her workplace, soliciting donations for her family. He reportedly raised at least $100, though it remains uncertain whether this money was genuinely delivered to her family or if the initiative was a scam. The man's identity was never disclosed. Optimistically, this gesture might reflect Amelia's cherished status within the community. On September 20, an estate sale was organized to liquidate her possessions, yet it is unclear if any of the proceeds benefited her sons.

In the wake of their mother’s death, the lives of Gary and Steven underwent significant changes. The boys were taken in by relatives, uprooted from their familiar surroundings and thrust into new environments. Steven recalls being moved to his aunt's place in Middleway and then to his grandfather's, before settling with an uncle on a farm in Leetown. This period of their lives was marked by instability and adjustment, as they navigated their grief and the challenges of adapting to new homes and caregivers.

Living on the farm with their uncle brought a degree of stability and normalcy to the boys' lives, although it was a stark contrast to their life with Amelia. Despite the challenges of taking in two more children into his already full household, their uncle cared for them and taught them the values of hard work and self-reliance. Steven acknowledges that his life could have been much worse and is thankful to his uncle for providing them with a home.

Steven shared that during his time as a student at Jefferson High School in Shenandoah Junction, he was actively involved in the Future Farmers of America (FFA) and frequently took part in agricultural jobs and other farming activities, no doubt influenced by his new life of the farm. He continued his agricultural work throughout high school and for nearly a decade afterward. Steven eventually transitioned from agriculture into a truck driving role, and then on to a career as a machinist. Later, he moved into the flooring industry, where he concluded his professional journey. Now, Steven enjoys retirement in the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia, content with the life and career paths he has pursued.

Following his mother's murder, Gary Wilson's life spiraled into increasingly troubled waters. Steven recalls that by the age of 12, Gary had already delved into criminal activities, notably stealing a car from the Jefferson County Jail parking lot. His brush with the law during these formative years only intensified with age. By tenth grade, Gary had all but abandoned his education, and after a series of confrontations, he was eventually asked to leave by the uncle who had offered them refuge on his farm.

Gary's adult life was marred by a continuation of legal troubles that had begun even before his mother's tragic death. Reports from the early 1980s in the Spirit of Jefferson newspaper document a litany of charges against him, from forgery to breaking and entering, climaxing with a dramatic jailbreak in 1984. Gary was part of a quartet that managed to flee the Jefferson County jail, capitalizing on a moment when a jailer inadvertently left a door open. The subsequent manhunt concluded with Gary's apprehension in Sharpsburg, Maryland, a saga that captured headlines as far away as Easton, Maryland. Whether Amelia's influence could have altered Gary's path remains speculative. While Steven doubts it, those acquainted with Amelia believed she was endeavoring to steer him right, efforts cut short by her death.

Decades later, Gary's current location is a mystery. Steven, reflecting on the divergent trajectories of their lives, reveals that it has been over 40 years since he last had any contact with Gary. The scant information available about Gary's later life includes a vague reference from a law enforcement relative about an arrest in California more than three decades ago, leaving more questions than answers about his fate. (Editor's Note: An update at the end of this article provides new details about Gary's whereabouts.)

In 1988, Steven Wilson discovered he had a sister, Linda Minnick, and another brother, Steven Pyles, both of whom had been adopted at birth. Linda, aware of her adoption, had been searching for her birth mother when she learned about her three brothers: Steven, Gary Wilson, and Steven Pyles. That year, Steven and Linda were reunited. Linda, born two years after Steven, joined forces with him to locate their other brother, Steven Pyles, who was born when Steven was five.

Within a year of initiating their search, the siblings achieved a heartfelt reunion nearly two decades after their mother's death. Initially, while Linda resided in South Carolina, they found that Steven Pyles lived less than 60 miles from Steven. This discovery eventually led the brothers to work together as truck drivers for the same company. Tragically, Linda succumbed to COVID-19 in 2021. Reflecting on their family's past, Steven expressed that he harbors no resentment towards his mother for placing his siblings up for adoption, understanding that raising four children alone would have been beyond her means.

The murder of Amelia Wilson triggered a cascade of events that profoundly affected her children, causing ripples of consequence well beyond her death. The loss abruptly ended the childhood of Gary and Steven, plunging them into a world of grief. Their lives, shaped by adversity and resilience, highlight the deep impact of their mother's death.

As they grew up without their mother, Steven and Gary's lives took markedly different paths. Steven found comfort and purpose in his work, leading to a tranquil retirement, while Gary's life became entangled with legal issues. Their paths illustrate the varied ways people deal with loss. A later reunion with their siblings, Linda and Steven Pyles, provided a fleeting sense of closure and reconnection, long withheld.

Now 64, Steven Wilson, reflecting on the more than five decades since the tragic event, contemplated what he would say to his mother if given the opportunity. His heartfelt response: “I love you, mom.”

The Wilsons' story underscores the extensive effects of violence, not just on direct victims but on those left to piece together their lives. Although Amelia Wilson's murder remains an unsolved case, its memory has dimmed in Charles Town, now largely recalled by older generations. This fading memory reflects the community's slow healing process. Ultimately, Amelia Wilson's legacy is a reminder of the lasting impact on her family and the critical importance of seeking justice and closure. This tragedy highlights the human spirit's resilience and the possibility of finding peace amidst grief.

Update on Gary Wilson's Fate

After years of not knowing where Gary Wilson was, a recent discovery has solved the mystery. On March 26, 2024, the owner of an empty vacation home in Rimforest, California, found the decomposed body of 67-year-old Gary Eugene Wilson on the couch in the living room when she visited the property for the first time since 2023.

The San Bernardino County Fire Department's paramedics were called to the scene and confirmed that Gary had passed away. The circumstances surrounding Gary’s life in recent years and how he ended up in the vacant home remain unclear. His death, which occurred unnoticed, brings a close to the questions about his fate following the murder of his mother and his spiral into lawless behavior. Gary's death, found alone and in California, encapsulates the unfulfilled and perhaps fitting end to his life, far from his roots.

I have compiled and shared all the sources that informed this article, in the hope that this information might contribute to solving the case and securing the closure it rightfully deserves. If you possess any evidence related to this crime, please reach out to the Charles Town Police Department at (304)-725-8484. Additionally, if there's anything you believe I may have overlooked or missed in this story, I encourage you to contact me directly. Your insights could be invaluable.