Swinging Party - The Death of Jim Stephens and Jeff McGrath

In 1967, a NYC patio hammock accident killed Jim Stephens and Jeff McGrath, altering survivors' lives. Stephens, a radio icon, and McGrath, an ad exec, were enjoying post-party relaxation when the tragedy struck. The incident left an indelible mark on their families and industries.

As 1967 dawned, it would unfold as a year of turbulence for New York City, marked by both cultural shifts and civil unrest. It was in this context that, in the early hours of May 2nd, a decision as simple as swinging in a hammock tied to a chimney on a New York City patio led to a catastrophic accident. This tragedy claimed the lives of Jim Stephens, 43, a revered voice in radio and television commercials, and Jeff McGrath, 38, a respected advertising executive. The incident cut short the lives of these two accomplished men and deeply affected their families, friends, and the professional communities they were part of, becoming a somber part of the year's tumultuous narrative.

The Dead

James David "Jim" Stephens, born James David Seluzetsky on October 21, 1923, in Baltimore, Maryland, was the son of Stephen and Eufemia Seluzetsky, Polish immigrants who spoke Russian. His upbringing, shaped by his parents' immigrant journey, likely instilled in him a strong work ethic and perseverance typical of first-generation Americans. James's formal education took place at Baltimore City College, where he studied for two years until he began working for the Glenn L. Martin Company in Middle River in 1941. Around this time, Stephens married his wife, Joan. In 1943, he enlisted in the Army, contributing to the World War II effort. A notable moment from his service includes a letter to the editor of the Baltimore Evening Sun, where Sergeant Seluzetsky expressed his views on the nonfraternization policy with German women shortly after VE Day in 1945.

After serving in World War II, Stephens embarked on a new chapter, entering the realms of radio and television and choosing to go by the name Stephens rather than Seluzetsky by 1947. This decision was likely influenced by several factors: the pursuit of smoother professional integration, a desire for social assimilation, or possibly to avoid the stigma associated with Russian-sounding names as Cold War tensions began to surface. Alongside his burgeoning career, he furthered his education at the University of Maryland and shared the stage with Helen Hayes in a radio production of What Every Woman Knows.

While the exact timing of Stephens' move to New York City remains a bit of a mystery, by 1958, records show he was already making his mark in the city. Mentions in Variety confirm his involvement in the voiceover industry, noting his work on ads for Pennsylvania Dutch Egg Noodles and Dorman's Swiss Cheese, as well as voicing Buster Brown in animated commercials. This early evidence of his presence in New York highlights the beginning of his influence in the advertising world.

By 1961, Stephens had expanded his repertoire, lending his voice to the documentaries Smashing of the Reich and Kamikaze. This particular narration offers a timeless showcase of his distinct voice, allowing modern audiences to appreciate his talent. Over time, Stephens' voice became a familiar presence across the nation, securing his legacy in the auditory landscape of America. Despite a personal profile that remained largely out of the public eye, his voiceover work made his voice recognizable to many even if they didn't know his name, underscoring the significant impact he had on the industry and marking him as a notable figure in the world of radio and television advertising.

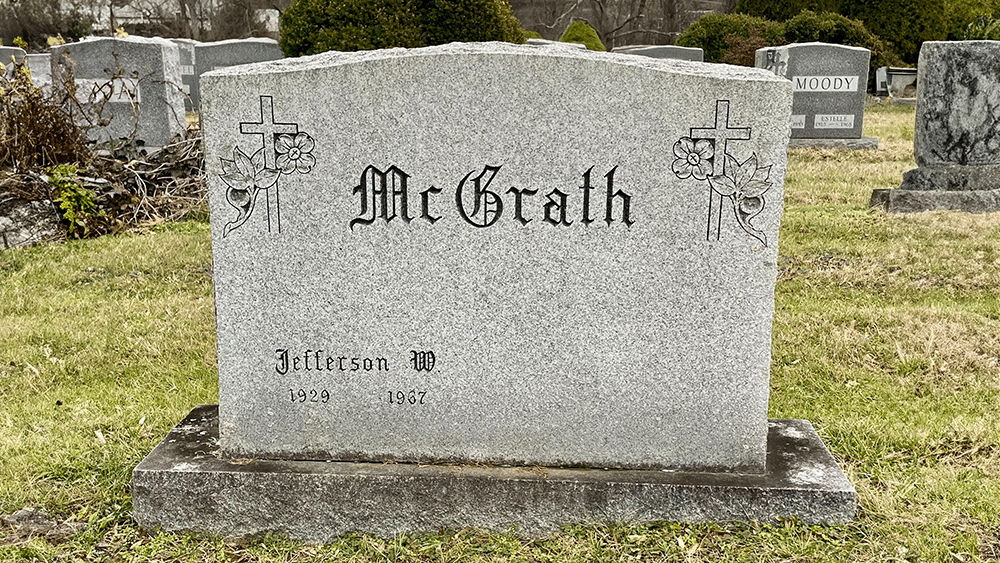

Jefferson William "Jeff" McGrath III was born on December 23, 1928, on Staten Island, New York, into a world on the brink of the Great Depression. He graduated from Curtis High School on Staten Island in 1947, where his yearbook hinted at a future in commercial art at the Pratt Institute. His high school years were marked by leadership roles and artistic pursuits, laying the groundwork for his career.

On September 9, 1950, McGrath married Lois Jean "Sis" Roberts. Although he was too young for World War II, he served for 23 months during the Korean War from 1951 to 1952 as a corporal in the US Army Signal Corps. The records do not clarify if he saw combat.

McGrath's journey from an ambitious art student to a copy supervisor at the prestigious Benton & Bowles advertising agency reflects his lifelong dedication and talent. His role combined his artistic skills and leadership abilities, showcasing the culmination of his dreams and hard work.

Outside of his career, McGrath was a devoted family man, living in Middletown, New Jersey, with Lois and their four children: Neal, Jill, Jeffrey, and Chris, six grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

The Incident

On that ill-fated night, after the annual "Christmas-in-May" party thrown by United Recording Company — a gathering that drew over 1,500 members from the advertising, radio, and television industries — Stephens and McGrath found themselves on the terrace of Stephens’ fourth-floor apartment in a brownstone at 55 West 53rd Street. They were in the company of Pricilla Tedesco, 27, and Madeline Jane “Janie” Nieland, 23, two young secretaries from Benton & Bowles who would emerge as the sole survivors of the night's traumatic end. As the official party dimmed past midnight, this small group sought to extend the evening's joy in the more private, yet equally spirited, setting of Stephens' penthouse.

The apartment's patio, a 30-by-15 foot space that had once served as a backdrop for a scene in the film How to Murder Your Wife starring Jack Lemmon and Virna Lisi, became their refuge under the expansive night sky. Opting for the simple pleasure of a hammock, their choice seemed harmless. As neighbors later recounted, the quartet was immersed in laughter, song, and the sharing of champagne, encapsulating a moment of pure revelry that belied the tragedy to unfold.

The tranquility of the evening shattered in an instant when the hammock, secured between a brick-and-mortar chimney and a wrought-iron trellis on the fourth-floor terrace of Stephens' apartment, became the epicenter of a devastating accident. Stephens, McGrath, and Nieland were lounging in the hammock, gently rocked by Tedesco, when without warning, the 15-foot chimney they were tethered to collapsed upon them. The merriment turned to chaos as tons of bricks and debris rained down, trapping all four beneath.

Nieland, recounting the harrowing details from Roosevelt Hospital, her voice laden with emotion, vividly described the moment disaster struck. "All of a sudden the chimney came down with a roar," she recounted. In the immediate aftermath, trapped beneath the debris, she could distinctly hear McGrath's labored breathing next to her. "I could hear him breathing in my ear. I told him to save his energy and take shorter breaths," Nieland remembered. Despite her advice for him to conserve his energy, McGrath's breaths ceased.

The response was swift from neighbors, including artist Steven Lasley, who, upon hearing the crash, raced to the scene. His account of the rescue effort underscored the chaos and the urgency of the moment. "I ran out to the terrace," Lasley said, "The others were buried in the rubble. I started clawing the bricks away and found a man with no face left" The sight that met him—a man grievously injured, likely Stephens—was so disturbing that he covered it with a towel, unable to face the prospect of more horror.

By the time Lasley reached the scene of the collapse, a sense of panic and chaos had already set in. Tedesco, having miraculously clawed her way out from under the rubble, was found in a state of hysteria and was running around the apartment and inconsolable. Meanwhile, Nieland, though partly buried, was more accessible. The men, Stephens and McGrath, were in a far grimmer situation, entombed under what was later estimated to be 7,500 pounds of bricks.

Lasley's quick response in the aftermath of the chimney collapse was pivotal; he managed to pull Nieland from the wreckage, discovering her unconscious but still breathing. Yet, the situation for Stephens and McGrath was far more dire. The weight of the rubble made their rescue not only urgent but exceedingly difficult. It was the observant eye of a night watchman, drawn by the disturbance, that enabled them to finally commence the arduous process of digging out the two men.

This collaborative rescue effort, while marked by a glimmer of hope for Nieland, ended in sorrow for Stephens and McGrath, who were both pronounced dead upon their arrival at the hospital. The contrasting fates of the victims that night underscore the randomness of survival in moments of crisis. While the women received treatment and were soon released, bearing the scars of the event, the loss of the men left a permanent void for their friends, families, and the wider community.

In the hours following the tragedy, the emotional toll on the families began to unfold. Joan Stephens arrived to perform the heartrending task of identifying her husband. Nothing could be found regarding the fate of Joan Stephens following her husband's death.

Meanwhile, in New Jersey, Lois McGrath received the devastating news that would forever alter the course of her life. Earlier that evening, her husband had called home at 5:15 PM, casually mentioning he would be home late. However, as hours ticked by without further word from him, what might have been a night of mild annoyance turned into a nightmare. The call to inform her of her husband's death shattered the normalcy of their family's life. Lois outlived Jeff by 49 years and would remarry in 1988, and spend her final years in Florida. Her final resting place would not be beside Jeff's, leaving one to ponder her reflections on his last moments.

The tragic incident that led to the untimely deaths of Stephens and McGrath was closely scrutinized by Charles G. Moerdler, the Buildings Commissioner at the time. In his detailed investigation, he pinpointed the absence of a crucial structural component—a heavy iron brace—as a key factor in the catastrophic collapse of the chimney. This brace, originally designed to support and stabilize the chimney at a 45-degree angle, had been removed, a decision speculated to have been made for aesthetic reasons. He noted that the chimney, devoid of this essential support, was ill-equipped to bear the additional load imposed by the hammock attached to it. Despite the absence of direct violations of the building code related to the accident, Moerdler took the opportunity to issue a stern warning. He advised against the use of architectural protrusions like chimneys as anchor points for hammocks or similar items, emphasizing that such structures are not intended to support external loads. This warning is as important today as it was back then, as countless deaths and life altering injuries have been caused by hammocks attached to structures not intended to support such lateral forces.

The Survivors

Priscilla Tedesco, born on June 25, 1939, in New York City to Joseph and Josephine Tedesco, grew up as a proud first-generation Italian American, one of three siblings. She grew up in Brooklyn before moving to Long Island, where she attended Hicksville High School. In 1969, two years following the life-changing incident, she married Walter Edwin Reichel Jr., himself a first-generation American with German roots. This union marked the start of a resilient partnership. Walter, possibly a colleague of Priscilla's at Benton & Bowles, was recognized in the 1972 edition of Who's Who in Advertising, hinting at their professional intersections. Together, they have created a legacy that now includes a son, Brad, and a grandson. Currently, Priscilla and Walter Reichel's enduring relationship thrives back in Brooklyn.

Madeline Jane "Janie" Nieland, born in December 1943 to James and Margaret Nieland, grew up as one of four siblings. She completed her education at St. Mary’s High School in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, graduating in 1961. Less than a year after the tragedy, she married Charles Joseph "Chuck" Paone in April 1968, in Perth Amboy. Their union brought two children into the world—Christopher James and Mariah Jane—and established a nurturing family life in Wilmington, North Carolina. The passing of Chuck in June 2020 tested Jane's resilience, marking a significant turning point in her life. Despite this profound loss, Jane has persevered, moving forward with her life in San Francisco, California.

The brownstone at 55 West 53rd Street, forever marked by a tragic hammock accident, stood as a silent witness to the passage of time until the 1990s. Its later years saw an unexpected chapter as part of the American Folk Art Museum in the 1980s, adding a layer of cultural significance to its history. The timeline of its demolition, however, fades into ambiguity, leaving a gap in the narrative of this storied building. In its place, a storage area for the Museum of Modern Art emerged, quietly serving New York's art community for over two decades. The eventual construction of 53W53, a testament to contemporary architectural ambition completed in 2019, marks a stark transition from the brownstone's historical charm to the relentless march of urban development. As the skyscraper reaches towards the sky, the memories of 55 West 53rd Street linger as a poignant reminder of the city's ever-evolving landscape—a reminder that, despite the physical disappearance of such sites, the stories and tragedies they housed persist in the collective memory, at least for a time. With the fading of firsthand accounts, the essence of what once was risks being overshadowed by the new, exemplifying the transient nature of collective memory.