A Journey Alone: The Tragic Tale of Paul Bowman

This exploration into an incomplete gravestone reveals the lives of Paul Bowman and Dorothy Moler and Roger Milbourne. Their ordinary yet poignant stories, from a fatal accident to a second marriage, unfold hidden tales from a small town's past.

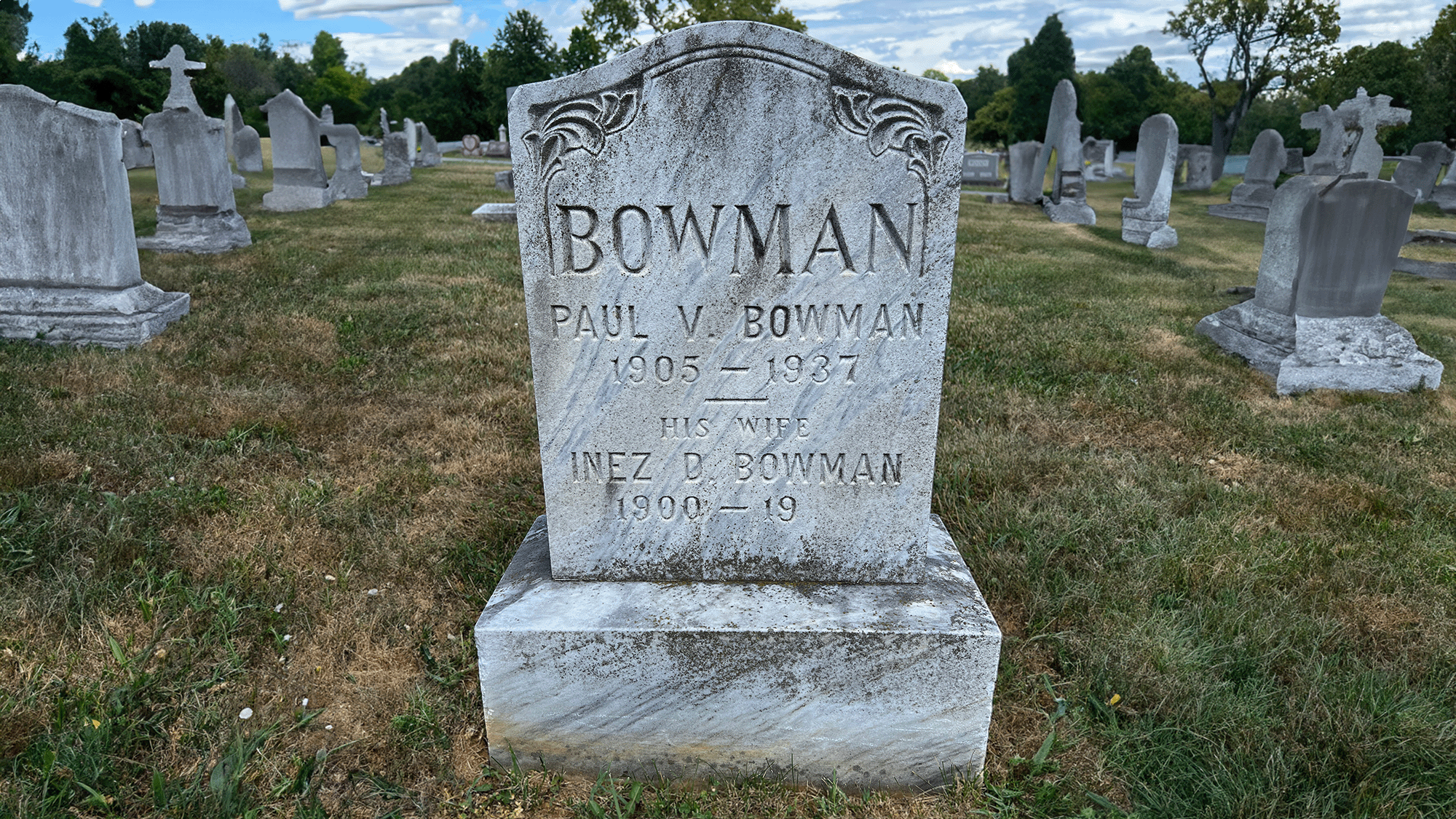

Last week, while strolling through Edge Hill Cemetery in Charles Town, West Virginia, an intriguing memorial caught my attention. It was a gravestone shared by a husband and wife; however, only the husband's life span was fully detailed, leaving the wife's details curiously incomplete. The wife's birth year was listed as 1900, making it almost impossible for her to be alive. The idea that her death date could have been casually overlooked seemed unthinkable. Stirred by this mystery, I decided to dig deeper – metaphorically, of course, not in the manner of a grave robber.

Our story's subjects remain largely enigmatic. They were not figures of public importance, and if it weren't for a single local tragedy, their names might have faded into obscurity completely. Yet, because of the unique practices of small town newspapers at the time, which documented daily activities and social visits as a form of community building and due to limited news scope, we gain some visibility into their lives. These detailed records serve as a window into the past, shedding light on what might have otherwise remained unknown.

The narrative unfolds starting from the scant information inscribed on a gravestone: Paul V. Bowman (1905-1937) and Inez D. Bowman (1900-19__). This was my only lead to their untold tale.

The gravestone's first inscription is dedicated to Paul Vernon Bowman, who was born on December 1, 1905, in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. In his youth, Paul acquired a slew of awards at the Morgan's Grove Fair Premiums for a variety of items including top-notch sweet pickled melons, rusks, and table pumpkins, among others. Apart from these accolades and a handful of social visits mentioned in local newspapers, there is little additional information about his personal life.

Unraveling the mystery of the second inscription. Inez D. Bowman, and her subsequent fate required some parsing of genealogical records. Through my research, I discovered that she was originally known as Dorothy Inez Moler from Moler Crossroads, Jefferson County, West Virginia. Her birth records stated December 24, 1900, as her date of birth, although her obituary indicated December 21, 1900. The reason behind the swapping of her first and middle names on the tombstone remains an enigma. However, all unearthed records consistently referred to her as Dorothy, and hence, I will do the same for the rest of the story.

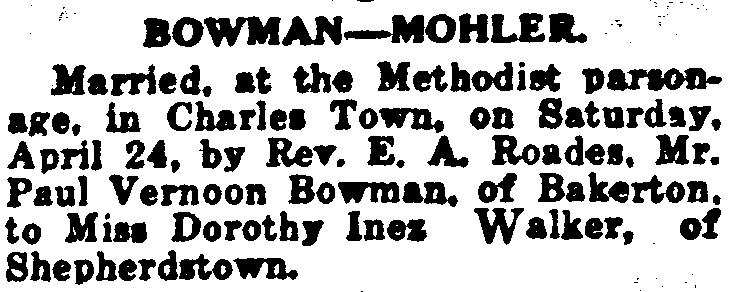

Records show that Paul and Dorothy wed in a ceremony at the Methodist Church in Charles Town, West Virginia. The service, which took place on April 24, 1926, was conducted by Reverend Edward Amiss Roades. Their marriage license stated Paul to be 21 and Dorothy 22, when, in fact, he was 20 and she was 25. The reasons for this discrepancy in their stated ages remain a puzzle. Was it intentional or a simple mistake? I attempted to verify if there were any marriage age restrictions in West Virginia during that period that could explain this, but was hindered by my lack of access to a law library. However, I discovered that the minimum age for marriage was 21 in Pennsylvania at that time, suggesting a similar rule might have been in place in West Virginia.

From historical news reports, we know that Paul worked as a scaler for the Standard Lime and Stone Company's limestone mine in Martinsburg. His job, which he had held for roughly a year, involved clearing loose rocks, debris, and overhanging material from the mine walls. Unfortunately, his life met a tragic end on the night of March 25, 1937. While toiling in the underground mine, a falling stone from approximately 30 feet above struck Paul, instantly killing him and fracturing his skull. The same incident resulted in severe injuries for two other men: Carroll Saville from Hedgesville, who was hurt so badly that his leg needed amputation, and Charles Polk from Pikeside, Berkeley County, who escaped with only bruises.

Paul's funeral took place the following Sunday, March 28, 1937. It was officiated by Reverend Dr. Giles Granville Sydnor of the Charles Town Presbyterian Church at Dorothy's parents' house and immediately followed by his burial at the Edge Hill Cemetery. This brings us back to the curious gravestone. The inversion of Dorothy's first and middle names on the tombstone, as compared to the official records, prompts me to speculate whether someone else may have arranged the marker. Additionally, the pre-filled century of her death raises questions about why she would restrict herself in such a manner.

As 1937 unfolds, Dorothy finds herself a widow at just 36. What she did in the ensuing years remains vague, with the local newspaper merely mentioning her presence at birthday parties and social events in the area. There are no records of her employment during this time. Almost exactly eleven years after Paul's untimely demise in the mine accident, Dorothy marries again.

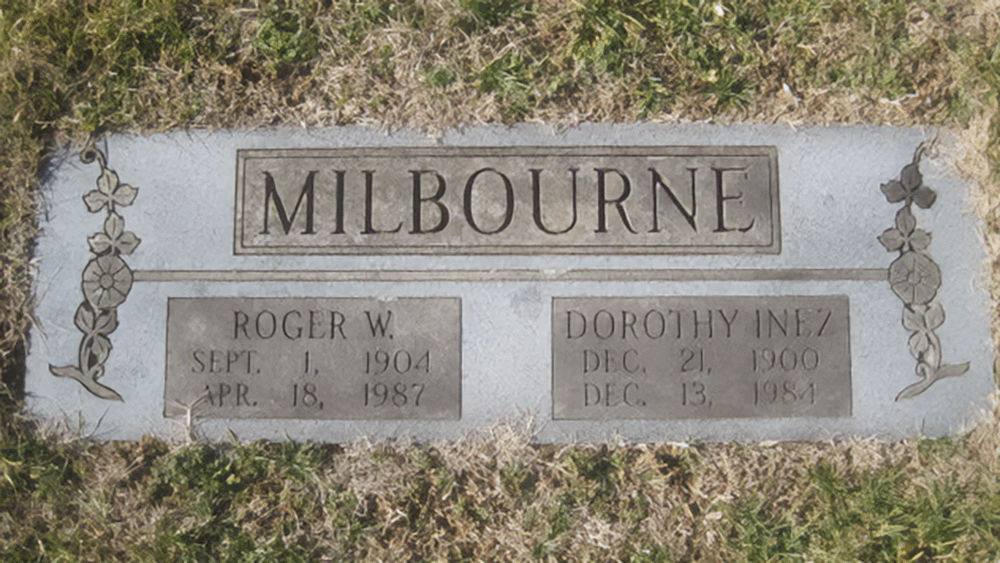

Her new husband is a local postman from Charles Town, Roger Williams Milbourne, born on September 1, 1904.

The couple were wed on March 16, 1948, by Pastor Dr. Paul B. Watlington Jr, at the First Baptist Church in Hagerstown, Maryland, a location just beyond the state border. The reason behind their choice of a different state for the marriage ceremony remains a mystery. The local paper carried no announcement of their nuptials, only a marriage certificate filed in the Washington County Courthouse attests to it. At the time of their marriage, Dorothy was 47, and Roger was 43.

Roger's life in Charles Town appears to have been simple and straightforward. According to the local paper, he consistently made the honor roll throughout his school years, suggesting a sharp intellect. In 1922, he was recognized as a member of the Charles Town High School football team, earning a "C" monogram for his consistent effort during the season.

Military records show that Roger didn't participate in World War II, but they don't specify why. His marriage license indicates that his union with Dorothy was his first.

Roger owned a sizable home at 705 S Samuel Street in Charles Town, as demonstrated by the numerous ads he placed seeking housekeepers and cooks prior to his 1948 marriage. Dorothy would continue to live in this home for the remainder of her life, as evidenced by her obituary which lists the same address.

Roger's mother, Virginia Strickler Milbourne, passed away less than a year after his marriage, suggesting that the house might have originally belonged to her and was inherited by Roger.

Interestingly, Roger's life was seemingly unremarkable in contrast to his brother's. Harvey Lee Milbourne, Roger's sibling, was a distinguished World War I veteran attaining the rank of Sergeant First Class and a seasoned diplomat with a 20-year career. One can't help but wonder whether Roger felt overshadowed by his brother's accomplishments.

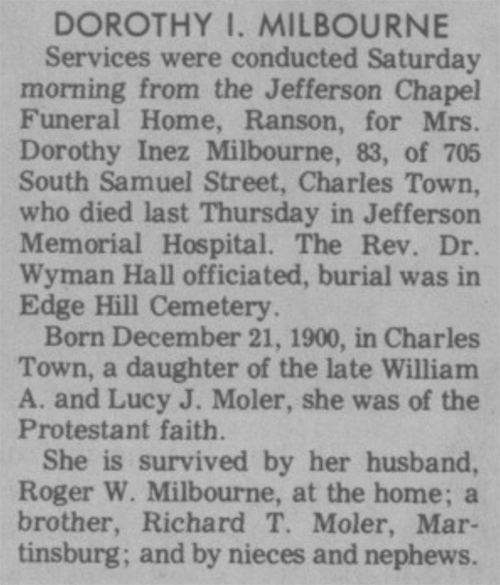

Little more is known about Dorothy's life except for a handful of social mentions in the local paper until her passing at the age of nearly 84 on December 13, 1984.

Contrary to what you might be assuming, Dorothy was not laid to rest next to Paul. Instead, her final resting place was in a separate plot, in a different section of Edge Hill Cemetery in Charles Town, next to a designated plot for Roger. Notably, her obituary doesn't mention Paul, listing only "nieces and nephews". This essentially erased Paul from her life's final chapter and left him alone under an unfinished tombstone. Whether this was Dorothy's expressed wish before her demise or Roger's decision remains unknown. Roger passed away less than three years later, at 82, on April 18, 1987, and was laid to rest next to Dorothy under a joint tombstone.

Searching for Roger's obituary proved fruitless. Strangely, the Spirit of Jefferson archive for the year 1987 is absent, leaving us uncertain if an obituary was published at all. However, even if one was found, it's unlikely it would alter the narrative. Given that Roger outlived all his siblings and had no offspring, it's plausible that no one was left to draft an obituary for him.

And that's the story behind the unfinished shared tombstone in a cemetery that led to a search for the truth. I appreciate you accompanying me on this exploration of the seemingly ordinary, yet subtly tragic lives of three individuals from Jefferson County's history. If there were any scandalous details or intriguing tales, they have been claimed by time, else they would have been shared here. Although they had no children and there might be few people who still remember them, their seemingly unremarkable lives still deserve a moment of remembrance. Let this serve as a reminder that every name etched in stone holds a story worth telling, no matter how ordinary it may initially appear.